The Basics of Induction Heating

Induction heating generates heat inside a conductive material by exposing it to a alternating magnetic field.

When alternating current flows through a coil, it produces a time-varying magnetic field. Placing a metal object inside this field induces electrical currents—called eddy currents—within the material. These currents encounter resistance and convert electrical energy into heat.

Unlike flames or furnaces, where heat moves from the outside inward, induction heating makes the material itself the source of heat. The result is a faster, cleaner, and more efficient process.

The Physics at Work

The effectiveness of induction heating depends on how the electromagnetic field interacts with the material. The frequency of current alternation influences how far the heat penetrates, with lower frequency allowing deeper heating and higher frequency producing more surface-focused effects.

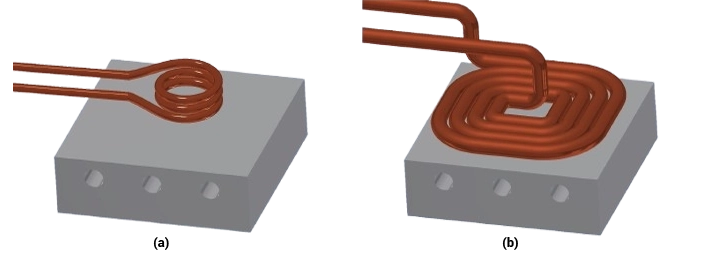

Material properties also shape the response. Conductive metals like copper and aluminum behave differently than magnetic alloys such as steel. The design of the coil adds another layer of complexity, since its shape, number of turns, and position relative to the workpiece determine how the field spreads and how uniformly the part heats. Finally, the amount of power applied to the coil sets the rate at which heat builds inside the material.

Why Industries Rely on Induction Heating

Induction heating is widely used because it combines speed, safety, and precision.

Heating occurs in seconds, reducing production time and energy costs. Because the heat is generated only where needed, the process is more sustainable and environmentally friendly. It also eliminates flames and combustion gases, creating a safer workplace.

Another advantage is selectivity. Engineers can harden one area of a component while leaving the rest untouched. Automated systems add repeatability, which is essential for large-scale production.

Real-World Applications

Induction heating plays a role in both heavy industry and everyday life.

In manufacturing, it supports hardening, annealing, and tempering. Brazing and soldering benefit from local heat that protects surrounding material. In metallurgy, induction furnaces provide a clean, efficient way to melt and forge metals.

The same principle even powers induction cooktops, where the cookware itself becomes the heating element. From steel plants to kitchens, induction heating adapts to very different needs.

Readers interested in related processes may also find our blog on transformer efficiency insightful, as it explores how heating and losses affect power delivery.

Engineering Challenges Behind the Process

Despite its benefits, induction heating is not without difficulties.

Achieving uniform heating requires precise coil design, otherwise hot spots and uneven temperatures may appear. Material properties, thickness, and shapes complicate system design further.

Thermal cycling is another concern. Rapid heating and cooling can introduce stress, warping, or cracking in sensitive parts. Engineers also face trade-offs between efficiency and flexibility.

Custom coils maximize performance but may not adapt well to new designs.

Even the coils themselves need careful management, since they often require active cooling to survive continuous operation.

Where Simulation Comes In

Designing induction systems is complex because frequency, coil geometry, materials, and cooling all interact in nonlinear ways.

To manage this, engineers frequently rely on electromagnetic simulation to predict heat distribution, penetration depth, and potential inefficiencies before physical testing begins.

These types of problems are often studied with EMWORKS EMAG, which helps engineers refine heating strategies earlier, reduce costs, and improve efficiency while minimizing wasted iterations. A deeper dive into this topic can be found in one of our induction heating application notes, which walks through simulation-driven design in more detail.

Final Thought

Induction heating is a clear example of physics applied to real-world needs.

By generating heat directly inside materials, it delivers speed, cleanliness, and efficiency unmatched by conventional methods. For engineers exploring these challenges, EMWORKS EMAG offers the tools to analyze induction heating as part of broader electromagnetic design studies. From metallurgical plants to home kitchens, induction heating continues to demonstrate how electromagnetic principles—and the right tools to study them—shape the way we design, manufacture, and live.

To continue exploring, visit our Resource Center for blogs, application notes, and guides on electromagnetic design.